Adventures of a long-distance Rider

•Posted on September 18 2021

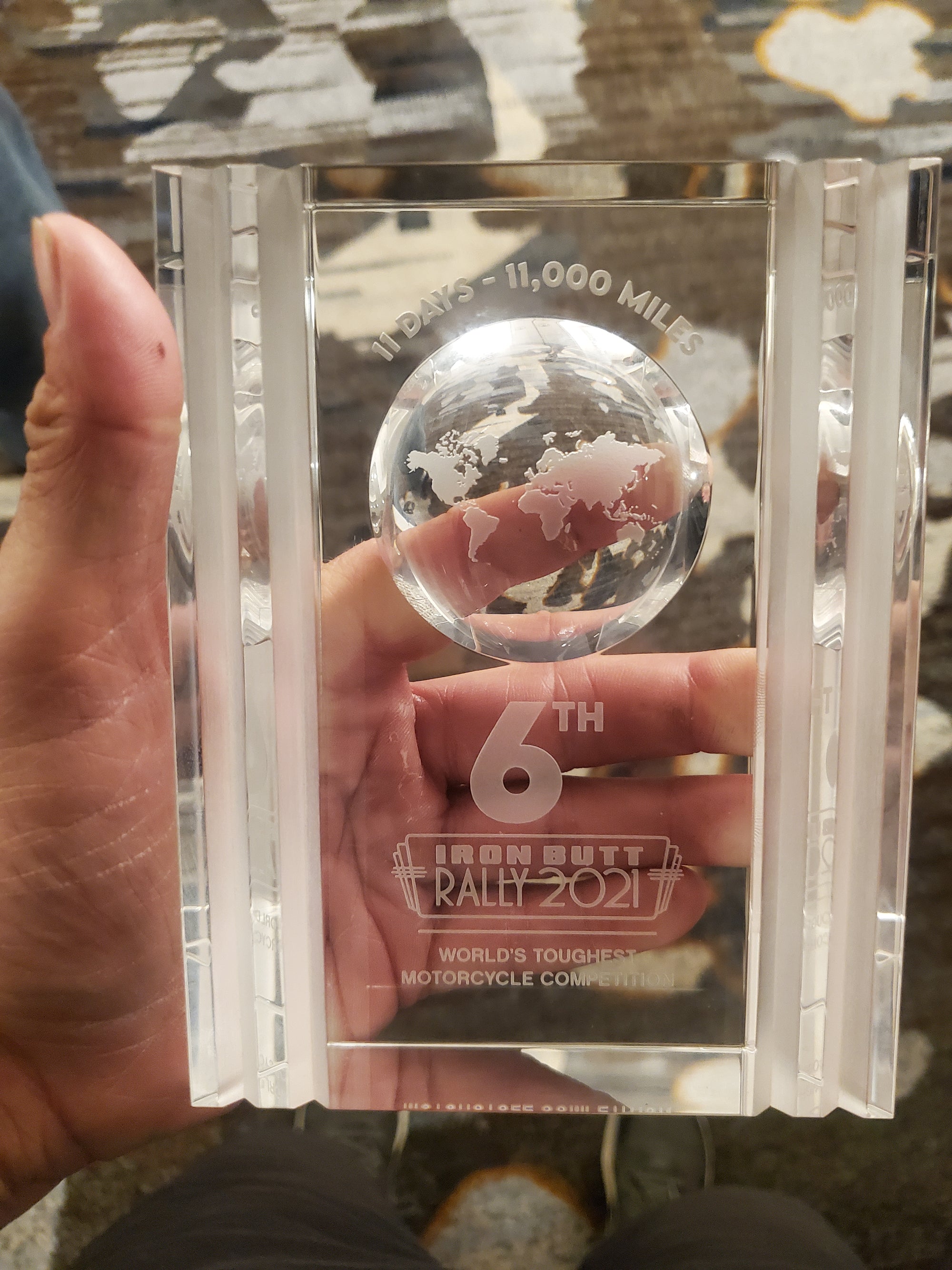

Man, what a ride! This year saw my sixth running of the 11-day, 11,000 mile Iron Butt Rally.

I’ve had a few minor issues in my rally career – a few flats here, one blowout that left me stranded in the middle of Saskatchewan, Canada, but nothing insurmountable. I’ve even managed to pull of a few podium finishes, including a win in 2019. But this year? This year I made up for a dozen years of relatively smooth sailing by cramming just about every possible kind of bad luck I possibly could fit into one rally.

I had installed my new MC Cruise system on my Yamaha FJR shortly before the rally (having installed on TEN years ago on my husband's Yamaha - he loves it!) and I was really looking forward to putting it through its paces on a massive scale. All of my previous endurance events had been run without cruise control, so I was definitely enthusiastic about the upgrade. Aside from that, the FJR has been my faithful rally bike for nearly 300,000 miles and required very little to be battle ready. My 700 mile trip to the starting line was relatively uneventful and the MC Cruise was a real treat on the wide open roads of the American Midwest. I say “relatively uneventful” because as I hit Provo, Utah, where the rally was to begin, my bike began overheating. I found seriously damaged radiator fins to be the likely culprit and, with only days till kickstands up and no replacements readily available in the US, I was just going to have to top off with Water Wetter and hope for the best.

The rally itself actually started off great, for all of about six hours. Just over 25% of the way through the first of 11 days, I picked up some road debris which caused my rear wheel to lockup. Running at a rather spirited pace on a secondary road, I rode it out for nearly 200 yards before somehow – incredibly – coming to a stop without going down. Still ramped up on adrenaline but immobilized in the middle of the shoulderless two-lane road, I managed to get the debris cut loose and the bike rolling before I was hit by a passing semi. My excitement was short lived, however, as it became evident that my “rolling” was really more of a gallop. The protracted skid had taken my tire from brand new to worn past the cords in a matter of seconds.

This was Monday in rural Idaho; most motorcycle shops are closed Monday, and the only open shop was a nail-biting 45 miles away along an 80mph stretch of interstate. Under any other circumstances there is no possible way I would have continued riding, but I wasn’t ready to throw in the towel on my sixth IBR before sunset on the first day. I spent an hour white-knuckling along the shoulder of the freeway, bouncing along and smelling hot rubber as my tire deteriorated further while commuter traffic whizzed by at twice my speed.

Somehow, miraculously, the tire remained intact long enough for me to reach the shop just a few minutes before closing. I pulled off the wheel in record time and rushed in to assess my replacement options. They were soft, softer and softest – road racing compound – but they were black and round, making them a significant upgrade from my current situation.

I had my spare wheel with a brand new rally-worthy tire waiting for me at Checkpoint Two, still six days away, so I picked the best of my bad options and crossed my fingers that this tire would go this distance.

Spoiler Alert: It did not go the distance. Five days and some 6,500 miles later it had given all it had to give. Unfortunately for me, with Checkpoint Two looming, I had to knock out 1,500 miles in the next 26 hours if I wanted to avoid my first ever DNF.

This being 7pm on a Saturday night, the odds of finding a shop to sell me a new tire were not in my favor. Plan B: Find someone with a compatible FJR somewhere between Minnesota and Alabama who was willing to swap wheels with me. Because the Long Distance community is awesome, I found a willing donor a few hundred miles away just outside of Chicago. My heroes make the 80 mile trek from their town to meet me at 1am just off of my planned route. What should have been an easy 15 minute swap became an unexpectedly complicated 90 minute ordeal as we uncovered some unanticipated fitment issues with the wheel as it came from an earlier year of FJR.

With some creative use of inappropriate tools along an impressive amount of inappropriate language, we managed to overcome the fitment issue and get the donor wheel installed. I hit the road with just enough tread to get me to the checkpoint, grateful for the amazing selfless folks who make this community great.

As I shook loose of pre-dawn Chicago and traded the high speed highways of the west for small, congested tracks of the east, it was painfully evident that my overheating problem had not magically rectified itself. And I do mean “painfully”. The Gen I FJR runs pretty darn hot to begin with, so adding in a radiator issue meant the air blowing through my engine compartment was hot enough to cause burns on my legs. It was no longer just a problem in stop-and-go traffic either; a section of road in Kentucky, tight and twisty and beautiful any other time, had me overheating even as I moved along at about 25mph presumably because I was stuck behind a truck. There was little I could do to address the situation on that remote patch of earth and once I was able to pass the temp backed off a notch, but still… it was cause for concern and definitely impacted my routing decisions going forward. If I didn’t DNF from a white-knuckle lockup or riding 500 miles in a deluge on a tire which was well into the cords, I sure as heck didn’t want to succumb to a grenaded engine. At this point in the rally I had written off all hopes of a Top Ten finish and my modified goal was simply to avoid a DNF at all costs.

I reached the checkpoint that evening a few minutes before the penalty window and went about servicing my bike. I’d hit a bonus earlier that day which was situated at the end of a long, steep, treacherous dirt road cut into the famous red clay of the south. Apparently I’d gathered enough of the mud and clay to gum up my rear brake pedal because, although they were fine at the wheel exchange 18 hours earlier, the rear brake pads were now at the metal. There was nothing I could do about it at 9pm on a Sunday so I swapped out my rear wheel with the spare that I had staged there, cleaned and lubed the offending pivot, and called it a day. When the bonus pack for Leg Three was released at 4am the following morning, I identified a route which would offer decent points, generally avoid conditions which might aggravate my overheating, and take me a stone’s throw from my old hometown in California. I arranged for a friend to pick up a set of replacement brake pads and meet me along my route. Twenty nine hours and 2,200 miles later, I pulled into our prearranged meeting place; 29 hours and 18 minutes later I pulled out with new brake pads installed, water jugs filled, and LD Comforts soaked and ready for a day of temps hovering around 110 degrees. I can try to avoid congested roads, but alas, I can’t control the weather.

I’d like to say it was all easy riding from there on out, but that’s just not how my 2021 IBR was destined to play out. If there was a construction zone, I got stuck in it – 30 minutes here, 15 minutes there adds up fast. I had to drop some more far-flung bonus locations in order to ensure I could make the giant cornerstone of my big-point thread bonus series: Glacier National Park. In order to secure the points we were required to document being at both the West and East entrance gates; the most straightforward way to accomplish this was to ride through the park. Straightforward, yes. Fast, not by a long shot. I hit the west gate first thing in the morning and hoped for the best, and traffic was actually very courteous and relatively light right up until the road began its steep ascent along the mountain’s face. At that point three things happened simultaneously: Everyone mutually agreed that they would go 10mph instead of the 25-40mph posted limit, they would no longer use any pullouts regardless of how open and accessible they were, and my bike went immediately into full meltdown overheating mode. It was agony. I didn’t want to pull over to cool down because I was convinced it would never start again, and if there’s one place you really don’t want to have a serious breakdown (unless you enjoy paying exorbitant towing fees), it’s in the middle of a National Park.

I persevered. I pleaded, begged, swore and yelled. Finally as we neared the summit, the handful of vehicles in front of me either pulled off into the visitor’s center, or in a brief moment of apparent indecision veered just a tiny hair in that direction. That was good enough for me; I seized the opportunity to pass everyone in as close to a legal manner as one was likely to find given the circumstance. As soon as I cleared the rolling roadblock, I killed the engine, kicked it into neutral, and coasted. For more than 20 miles I let gravity and the cool air do the work, only twice having to restart briefly when other traffic slowed my momentum. It took more than 10 minutes for the temp to drop from six bars to five, and I was back in the normal range by the time I hit the sign at the East Gate. Somehow, miraculously, the bike restarted and continued on without missing a beat. She’s a good old beast, I’ll give her that.

In keeping with my rally so far, the last day was a wild one. Most of the afternoon was spent in a terrible storm with driving winds, blinding rain and a dust storm thrown in for good measure. I got pulled over, but by that point I just found so much humor in my string of bad luck that I didn’t even care. The cop was really nice, just warned me about lots of deer on the road up ahead and sent me on my way. I hit something in the wee hours of the night in the middle of the Nevada desert, something still unidentified but robust to send me into a full-on tankslapper. I thought “This is it. This is how my rally ends, with the finish line in sight.” But somehow I rode it out, took a deep breath, let my heart rate return to normal, and pushed on. I knew I wouldn’t place well, but I knew I would finish. Upon finally arriving at the finish line back in Provo I found huge blisters on both legs running from my upper calves to lower thighs, a souvenir from running 11 days and some 13,600 miles on a near-molten machine. The scars are still pretty noteworthy today.

Imagine my surprise when, in spite of absolutely everything – the mishaps, the mechanical failures, the just plain bad luck, I managed to pull off a 6th place finish. It is without question the hardest fought rally finish in my career and I am honestly stunned I managed to pull it off. I give credit in large part to the contributions of the endurance riding community who helped me keep my wheels turning in so many ways, big and small. Many people stepped up and selflessly offered and provided assistance in so many ways that it’d be impossible to include them all in this short overview, but I have no doubt I would have DNFed without their contributions. This type of event challenges riders and their equipment in so many ways even in the best of circumstances, but the upside to having terrible luck is that it generates way better stories, and that’s what sticks with you in the end anyhow. So here we are: Summer is winding down in the northern hemisphere, the FJR is being prepared for major repairs and it will live to rally on, and through it all my MC Cruise never missed a beat. At least that makes one thing that worked right this year!

Comments

0 Comments

Leave a Comment